The Curious Case of the Father of Emma Graham’s Children

Emma Graham (1851-1922) was the second, and youngest, daughter of Henry Graham (1819-1896) and Martha Ann Goodman (1811-1864). Emma herself had three children: Alice Graham (1872-??), Emma Roberts Graham (1882-19??) and William Roberts Graham (1883-1937).

The Birth Certificates

As can be seen below, the birth certificates of these three children have no entry for the father (click an image for a larger version).

Could the middle name “Roberts” given to each of the two youngest children possibly be a hint as to the identity of their father?

The 1881 and 1871 Census Returns

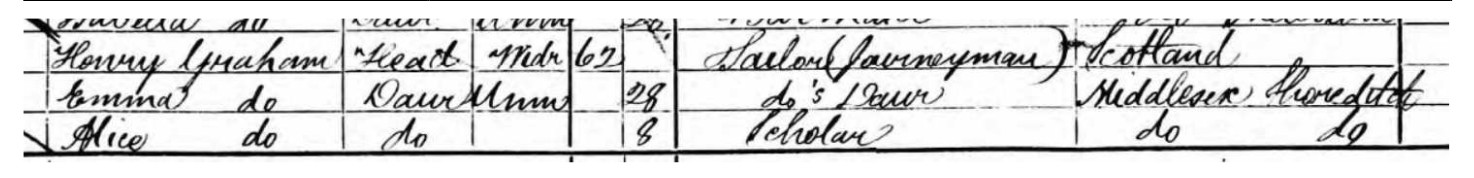

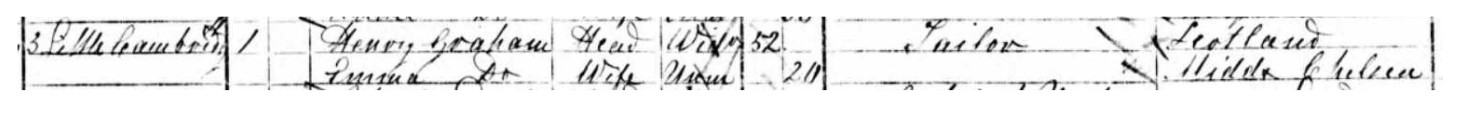

There is a strange entry in the 1881 census return made by Emma’s father Henry. Emma’s relationship to Henry is stated to be daughter. Alice’s entry is immediately underneath Emma’s, and her relationship to Henry is stated to be “ditto,” instead of granddaughter.

It is very likely that this was a genuine mistake, but is it possible that this entry was quite correct, and that Henry was indeed Alice’s father? The confusion is increased by the fact that in the 1871 census Emma was stated to be Henry’s wife, although at the same time was unmarried!

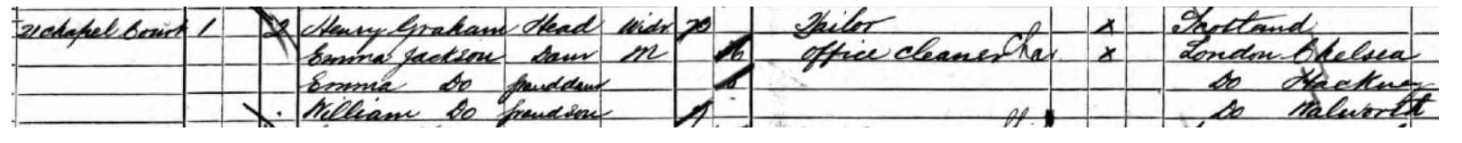

The 1891 Census Return

In 1891 Emma was living with her father, Henry, and her two youngest children (her oldest child, Alice, had married in 1890). In the census return Emma is said to be married, and she and both the children have the surname “Jackson.”

At first sight this seems to be straightforward. We presume that Emma married a Mr Jackson at some point in the preceding decade. This must have been after the children were born, since the surname Jackson does not appear on their birth certificates; if Emma were married at the time of their birth then her surname, at least, would not have been Graham. Consequently there is no reason to suppose the children were Jackson’s. His absence at the time of the census may have been due to his occupation, or his recent decease, or possibly marital breakdown. It seems relevant that a few months earlier at Alice’s wedding one of the witnesses was Emma Jackson, and it is reasonable to conclude that this was Alice’s mother. Note, however, that Alice’s surname at her wedding was not said to be Jackson.

However, no records can be found of Emma’s marriage to Jackson. Moreover, other records throw considerable doubt on the suggestion that such a marriage took place. Emma’s daughter, Emma Roberts, married in 1900, and at that ceremony her surname was stated clearly to be Graham. Her son, William, was still living at home in 1901, and at that census his surname was clearly stated to be Graham. But, most telling of all, Emma herself was married in 1895, to Bainbridge Davison Jones, and the marriage certificate clearly states that her surname at the time was Graham, and that she was a spinster.

No other evidence can be found of the existence of Jackson, and given the clear statements on Bainbridge and Emma’s marriage certificate we have to conclude that the assertion of her marriage to Jackson was false. It is not difficult to understand why she (or her father) might have invented such a story, given the prevailing negative attitudes at the time to unmarried mothers. There is a real possibility that Henry’s mother’s maiden name was Jackson, and if so this might have suggested the choice of name.

The Children’s Marriage Certificates

The statements regarding paternity on the marriage certificates of Emma’s three children are intriguing.

Each of them claimed that their father was deceased. Alice said that her father was William Graham, a bootmaker. William made a similar claim, adding the middle name Roberts. Emma, instead, said her father’s name was Robert Graham, and gave no occupation.

The attribution of the surname Graham to their father does not seem particularly significant. Assuming they did not want to advertise the illegitimacy of their own births, using their own surname was an obvious choice.

The middle name Roberts ascribed by William to his father is an unusual one. It is surely significant that the same middle name was given at birth to both William and his sister Emma. The question is, were these names for their father pure fiction, much like Jackson in the 1891 census, or do they provide a clue to their father’s real identity? In particular, do they suggest his surname was Roberts? In Spain to this day the name William Roberts Graham would immediately suggest parents surnamed Roberts and Graham.

|

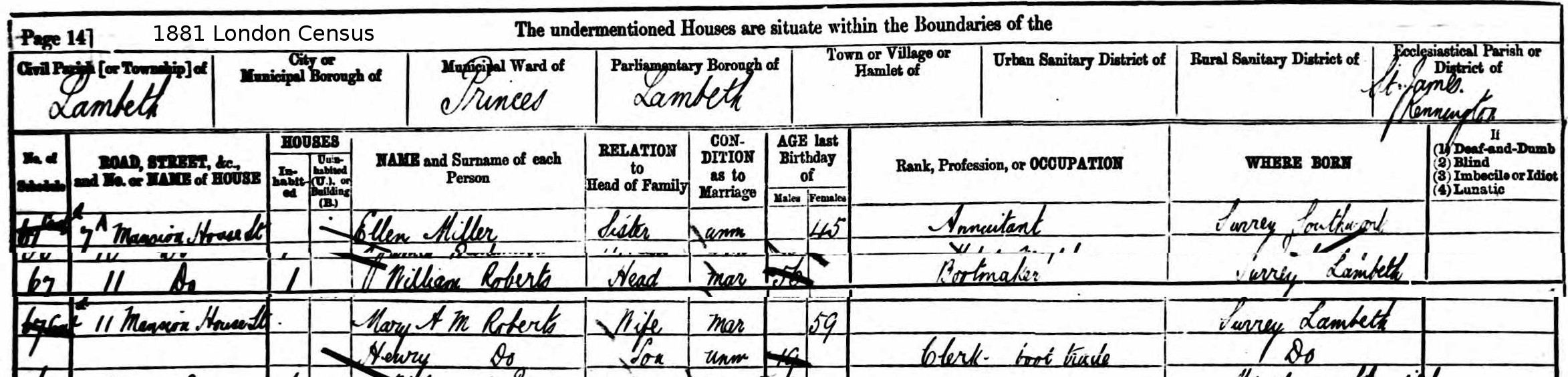

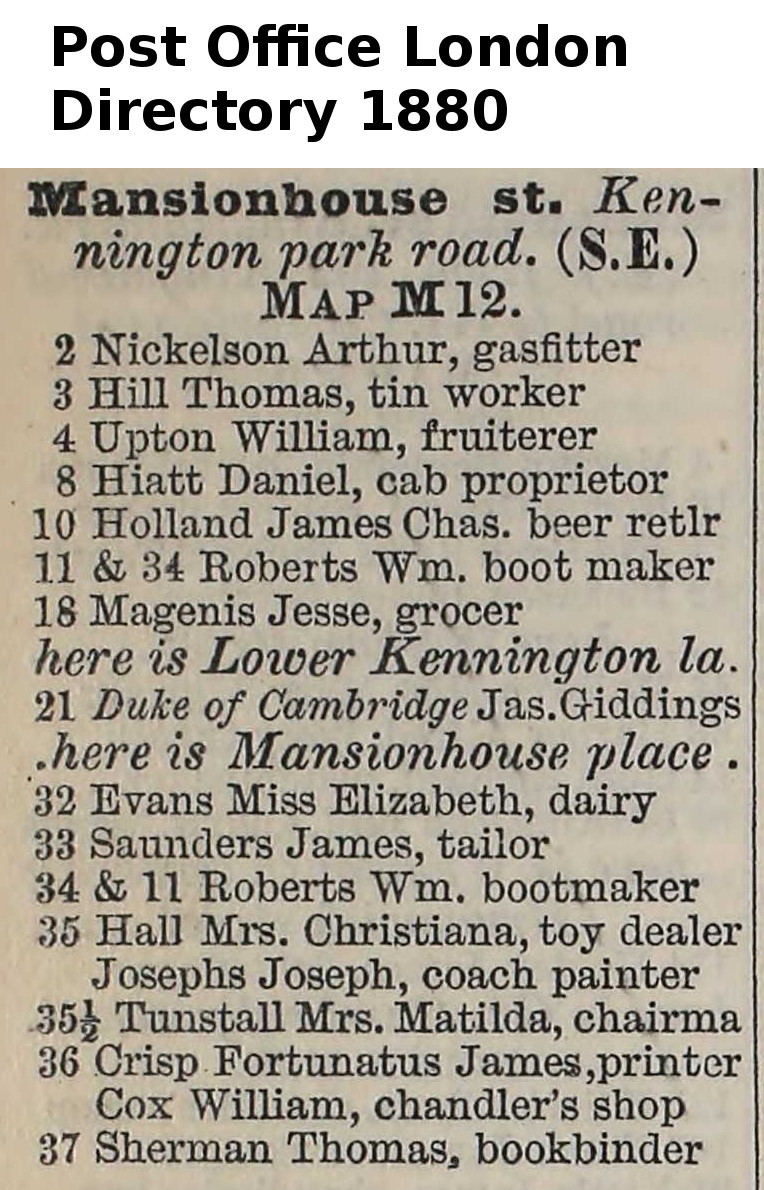

Interestingly there was a bootmaker named William Roberts living and working less than half a mile from the house in Steedman Street, Newington, where Emma gave birth to William. (See these extracts from the 1880 Post Office Directory and the 1881 London Census.) |

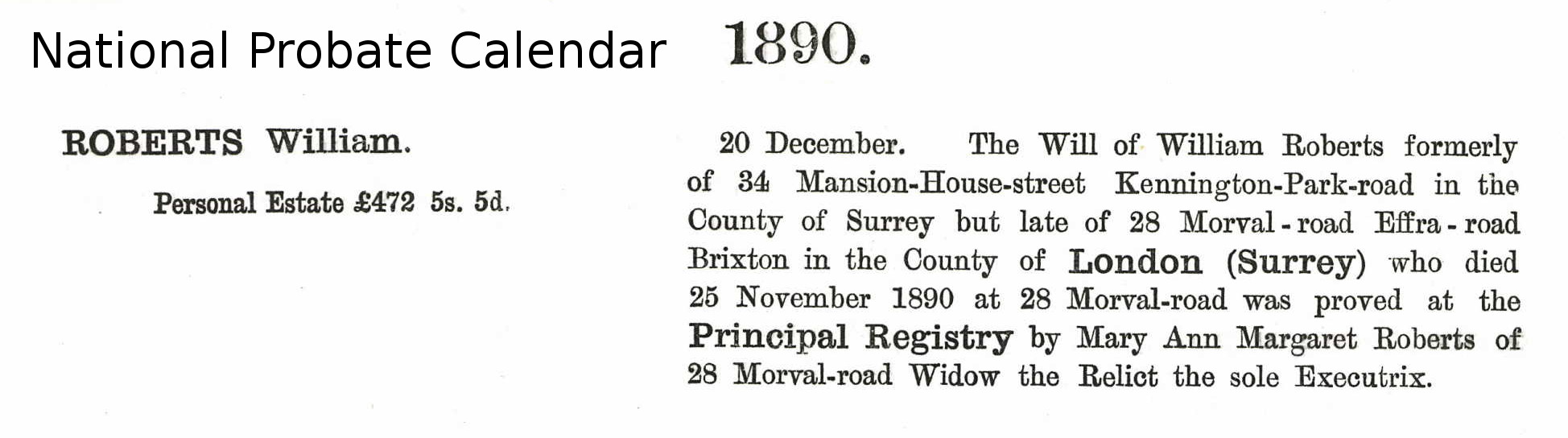

We note that the bootmaker William Roberts died on 25 Nov 1890, just a month before the first of the three children’s weddings.

Conclusion

Three main possibilities exist regarding the paternity of Emma’s children.

- Emma had multiple casual sexual relationships over a period of more than ten years, which resulted in her three conceptions. She may have been genuinely unsure of the identity of the father in each case.

- Emma had a long-term sexual relationship with a local man, probably a bootmaker. It is likely his full name included the names William and Roberts.

- Emma had an incestuous relationship with her father Henry, and her three children were his issue.

It is not possible to reach a definite conclusion. The use of the middle name Roberts for two of the children and also attributed by William to his father does seem significant, as does the stated occupation of bootmaker. These are simultaneously very specific and unusual. Together they perhaps give more weight to the second of the above possibilities.